Towards the end of Friday morning’s rehearsal session, EV Crowe said

“The space takes care of the dream, so we don’t have to worry about acting it.”

And later that day, Theresa Ikoko would say

“When I first got there I knew it was like limbo, that feeling I had.”

Before I started visiting The Site rehearsals – before it was even decided that I would – I dreamt about visiting it. In my dream it was blue, I’d known it would be, but instead of a singular rectangular space it was a series of three rooms, connected by heavy red velvet curtains. The kind of curtains that hang over our most traditionally-imagined stages. The show I was watching was all about nothingness, or maybe Big-N-Nothingness. There was something about a void, and a recurring zero. Huge, circular oh oh oh ohs made from white fluorescent strip lighting, as if handwritten by Tracey Emin, flashed across one of the walls. And then, after a short interval, we all had to get up and move into one of the other rooms, like a surprise promenade.

Except that in my dream, that caused the audience to fracture. I remember looking back through the gap in the red curtain and seeing loads of people getting their coats on and heading home. I had to shout back through the gap “Hang on you guys, there’s more play happening through here…” But the people didn’t turn back.

I don’t know what it means, although I’m fairly confident I shoe-horn it into at least three different arts-fables. Perhaps about form, or participation, or the way that the theatremaking process is so often obscured.

—

André Breton, the founder of the Surrealist movement, thought that dreams were where our imaginations could move freely. Our waking minds imposed a restrictive logic that could be cast off at night, allowing us to be our truest and most creative selves. Even if you think all that dream interpretation stuff is bollocks, it’s hard not to get carried away by the romance of the idea. And how great is this quote from Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto:

“Beloved imagination, what I most like in you is your unsparing quality.”

(Answer: very.)

You can draw a line – imagined, of course – from Freud and all his dream stuff at the end of the nineteenth century, through the modernist prose of James Joyce and Ulysses, then loop it around Breton and the Surrealists before landing in the theatre, at Samuel Beckett. Beckett, who placed such formal restrictions upon himself, actually translated a bunch of surrealist poems once. And productions of his texts, often so singular of voice and uncanny of aesthetic, are profoundly dreamy.

Watching Eileen Walsh perform EV Crowe’s ‘real life’ dreams in The Site on Friday, I was reminded of my visit to the Royal Court to see Not I in 2013: a disembodied voice emerging from an abyss, introspective even within its mania, and always with that Irish warmth, always deeply sympathetic. That night my eyes played tricks on me in the dark, like everything was moving, like the seats were sliding from side to side as if on castors.

When we take our imaginary pen and continue to trace the line from Beckett to EV Crowe, the dreams she is sharing in The Unknown push that imaginary line right round again, looping back to Freud, and to Breton’s unsparing quality.

—

Now that we’re nearly at the end of The Site’s programme, it’s possible to reflect on it as a whole. But, really, it has always been whole. Developed by Chloe Lamford as ‘an art project’ – neither mini-season, nor curatorial theme – it has existed within boundaries: not to restrict, but to provide freedom through safety. While across the alleyway, Anatomy of a Suicide and Killology are engaged in about five different and simultaneous conversations with one another, on a grand scale and in a public arena, the works in The Site advise each other in a gentle whisper. Its ‘wholeness’ is fundamental.

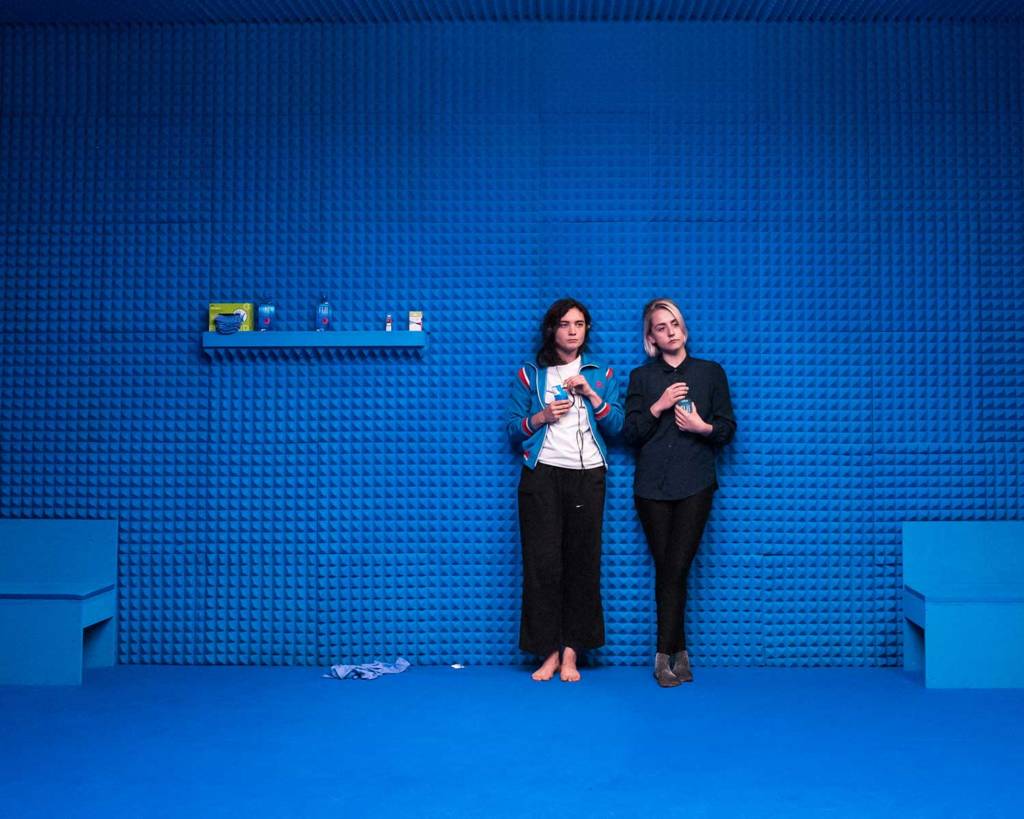

That wholeness manifest spacially, in that it was a singular room, separate and apart from the main theatre building; in terms of time, in that it was built to be temporary and will all be pulled down next week; but conceptually too. The principles of The Site – ten ‘facts’ prepared by Chloe and Lucy Morrison with input from the writers – were different from a mission statement or policy document, bonding the makers of the five shows to a shared process. Interestingly, only two of the ten covered the physical specifications of the performance space, while the other eight governed the form of the makers’ relationships: with the room; with the audience; with each other. This commitment was carried into the audience, who had to give themselves wholly to the The Site for the duration of their time in it, leaving phones in lockers before entering.

All this meant that The Site did not ‘open’ with the first performance of Lights Out in week one, or even on the first day of rehearsals or the day the first foam tile was stuck to the wall; it began with a question, from Chloe to the writers: what might this be?

—

What it was, for me, was a great surprise. A series of great surprises. I felt like I was moving from week to week like a small child, drugged from the dentist, rubbing her eyes and saying “wow” a lot. My cynicism has been shredded. My belief is amplified, doubled even. And I have learnt so, so much.

For starters, aren’t actors just unbelievable? I’ve heard people say that but it’s been so easy to dismiss as platitude. Watching a lot of theatre, show after show, night after night, your trust in both the form and the story means that the emotional obligation of performance is buried. Spending time in rehearsals, as actors go again and again, each time reaching into the psychological centre of a character that they’ve only just met, has shown me the coalface of acting, the hard labour, the vulnerability, the tireless bloody graft of it. Huuuuuuuge respect to actors. They must just be exhausted all the time.

Secondly, directing is alchemy. It’s not a job; it’s a personality trait. And for those in The Site who were wearing the director hat even briefly – whether Lucy Morrison or Chloe or Imogen Knight or any one of the five writers – it did not materialise as instruction or even necessarily intention. Instead, it was a suggestion here, a question there, and just knowing when to take a break and have a chat. This shouldn’t give the impression that it is anywhere even approaching simple. The opposite: it is a constantly evolving act of diplomacy. The UK’s Brexit negotiators could do a lot worse than observe a rehearsal room for a morning.

I’ve also learnt more about writing. For me, as a sort-of-critic inhabiting a sort-of-practice, blindly feeling my way between obtainable opportunities, this project has been another lurch forward within a perpetual stumble, but it turns out playwriting – however collaborative – is also that. Being completely honest for a moment, I think I have previously thought of playwrights as laying the foundations for something else. On Grand Designs, they’d be the guys who pour the concrete before the first ad break. But writing is research is writing. Story is the testing ground for idea. Of course I knew this theoretically, and I’m sure there are a bunch of playwrights reading this right now and saying “well OBVIOUSLY…” but all this time I have been so focused on THE SHOW. Even those shows which have really spoken to me and made me think deeply about something, I’ve been imagining that its makers wanted to present some kind of conclusion, some kind of thesis, and if I just looked hard enough I’d find their message and get a gold star.

What a fucking idiot. Theatre is the question: a limitless invitation, the sublime unanswerable.

A gestation, a meander, a daydream.

—

In the past few weeks, blogger Megan Vaughan have been visiting rehearsals for each of the five The Site shows, chatting to the writers and companies as they work, and running her fingers over the walls when no-one’s looking. Read Megan’s blog on: